|

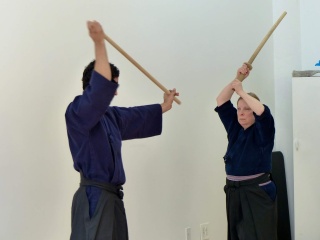

| Great day of training. It must have been 95F (35C) in the dojo, though. |

I

talk a lot about the benefits of budo. We go to the dojo and we

sweat. We work at improving some aspect of our skills every

time we enter the dojo. It doesn’t matter how long we’ve been

training or how old we are. My iaido teacher, Kiyama Hiroshi,

was still training in his 90’s. A friend of mine pushed himself to

improve his jodo to challenge for 8th dan when he was 90.He didn’t

make it to 8th dan, but he was pushing himself to improve until the

day he died.

Budo,

much like other Japanese arts such as chano yu

and

shodo,

makes three assumptions about practice and us. First, that perfect

technique can be imagined. Second, that we can always work to come

closer to perfection. Third, that we’ll never achieve perfection,

but that’s no excuse for not continuing to grow and improve.

All

of the streams of thought that come together to form budo assume that

human technique and character can, and should, continue to develop

throughout one’s life. Confucius, Lao Zi, Zhuang Zi, Siddhartha

Gautama (Buddha), all provided strands of thought and ideas to the

cultural stew of China and Japan. All of them assumed that people

could change, grow and improve at every stage of life.

The

Zhuangzi is filled with stories that emphasize taking your time and

learning things. The idea that learning and development never end is

intrinsic to the all of the lines of thought in ancient China that

used “way” 道

as

a metaphor for their school of thought. There

were a lot of them.

On

the other hand, there is a common idea in Western thinking that we

each have some sort of unchanging, immutable core or essence. I’ve

heard many people say “I can’t change. That’s just the way I

am.” or “I don’t like it, but that’s who I am.” Once

they finish high school or college, many people seem to think that

they are done growing, changing and evolving as a person. Thankfully,

there is no evidence to support any of this.

|

| A curated selection of the best of the the Budo Bum |

Everyone

changes, every day. Whatever we experience changes us. Little things

change us in little ways, and big things can be, as the saying goes,

“life changing.” Life never stops working on us, changing us,

molding us. We are not stone. We are soft flesh that changes and

adapts to the stresses it experiences. An essential question is

whether we are going to be active participants choosing how we change

and what we become, or are we going to be passive recipients of

whatever life does to us..

A

central concept of the idea of a Way, michi

or

do

道

is

that there is always another step to take, another bit of ourselves

we can polish, a bit of our personality that we can improve, and that

we can direct that change. This is true whether we are talking about

Daoist thought or Confucian thought or something in between. The idea

of a finished, unchanging human really doesn’t come up.

Budo

constantly reminds us that we aren’t finished growing, developing,

improving. Rather than declaring that we can’t change, budo is a

claxon calling out that we change whether we want to or not, and that

we can direct that change if we choose. Budo is about choosing

to direct how we change instead of just letting the circumstances of

life change us.

We

are making the choice to take part in how life shapes us from the

moment we enter the dojo, although I doubt many realize how much budo

can influence who we become when we make the decision to start

training. Good budo training should, and does, change us. Physically

we get stronger, more flexible, improve our stamina and develop the

ability to endure fierce training and even injuries. That’s the

obvious stuff. More importantly, budo changes who we are. It should

make us mentally tougher and intellectually more flexible. It should

help us to be more open to new experiences and ideas. It should teach

us that we can transform ourselves. It’s a cliche that budo

training makes people more confident, but it’s also true of good

budo training. You go to the dojo and you get used to people

literally attacking you, and as time goes on, you’re not only okay

with that, but you look forward to it. I don’t know anyone who

started budo training because they enjoyed being attacked, but it

doesn’t take very long before that sort of training, whether it is

done through kata

geiko

or

some sort of randori

or

free sparring, becomes something you look forward to with a smile.

Keiko,

the

formal term for budo practice in Japanese, is the highlight of my

week. The time I spend in the dojo practicing and doing budo never

tires my spirit. It exhausts my body, but my spirit always comes away

refreshed, recharged, and ready to deal with all the stresses of life

outside the dojo. Budo practice isn’t something we “play”. In

Japanese you never use the verbs associated with play when talking

about budo, and even judoka avoid words that emphasize the

competitive and focus on terms like tanren

鍛錬,

forging. Budo is about change; conscious, self-directed change.

The

wonderful thing is that once we learn how to change ourselves in the

dojo, we know how to do it outside the dojo as well. The discomfort

we get used to while pushing ourselves in the dojo teaches us how to

deal with discomfort outside the dojo. That’s one thing budo

doesn’t eliminate – the discomfort of changing. Self-directed

change is difficult and pushes us into places and situations that are

anything but comfortable. I can remember being a pugnacious jerk, and

dealing with disagreement and conflict as a win-lose scenario that I

had to win. It took a lot of time in and out of the dojo to learn

that just because there is conflict there doesn’t have to be a

winner and loser. There are lots of other ways to deal with

conflict, and I’m grateful to my budo teachers that I learned

something about conflict as something other than a zero-sum game.

Budo

has a lot to teach us about life, how we can change and adapt to the

world instead of letting the world change us. All the effort that we

put into learning the techniques and skills of budo also teaches us

how to direct an equal amount of effort into changing any aspect of

ourselves that we wish to confront. The budo path has no end

destination. We just keep working at it.

Special thanks to Deborah Klens-Bigman, PhD. for her editorial support and advice.

via Blogger https://ift.tt/nKOq2gk